A Pile o' Cole's Nat King Cole Website

Site Menu

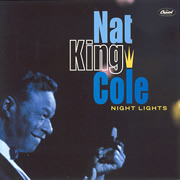

1956

Sessions

Sessions of 1956

January 4th

- Night Lights

- The Shadows

- To The Ends of the Earth

- I Promise You

- The Way I Love You

- Never Let Me Go

The distinction between a good orchestration and a great one is not always obvious, but it sure is profound. Another distinction we could make among many orchestrations is that one can either serve a passive or active role. In this case, that would be to say that it can serve song in a roughly functional way, or it could play a part in depicting it. More than a few of Nelson's greatest orchestrations were for Nat, and more than a few of those were of the latter kind. Night Lights is particularly literal.

The opening of Night Lights is another Nelson Riddle great, in its way as remarkable as any other he'd create. A lower "bop-bop" contrasted with a higher "bop-bop" is a really wonderful way to sound stupid, yet I'm thinking no one else listening to it has thought about it that way. These contrasting notes open the song and are followed by similar patterns in call-and-response between low trumpet "splats" and delicate celeste. They can also be seen as a sort of depiction of city lights in the orchestra's night; we see them as we go, and their glint and glare incidentally catch our notice.

Nelson picks just the right instrumentation at just the right tenor, as it were, so that neither the musical flow nor the implied thought-sound-picture are disturbed by these decorative notes. He seems to have derived them by abbreviating the song's "signature" phrases. Had another arranger first scribed this song, I can't help but think that if these notes existed at all, they would have been featured in a disjointedly gimmicky, even corny "pluck pluck" or "wah wah" or something. Had Nat arranged it for Trio however, I can sort of "hear" the opening scored, as he did on occasion, for a couple of guitar notes over bass in a way not entirely unrelated to this arrangement. Hard to say how writing for Nat subconsciously informed his work. But on from the speculation.

"Sweet dreams," Nat asks, "oh where did they fly to?" as a flute makes like a moth in the night, yet another active participation from the arrangement. The string lines drifting along during and after Nat's line "since I'm without you" suggest his free but adrift state as surely as the words. The drift breaks down behind the phrase "and whom can I cry to?" A pattern is repeated behind the phrase, "Remind me of bright eyes," and morphs into an exaggerated flight under, "white lies too good to be true." And so forth. Quite a bit of literal accompaniment and, as with the rest of this arrangement, richly varied in instrumentation.

The instrumental bridge sweeps into an overview that might be represented in cinematography by a pull way out of focus from lights and back into a sort of city-at-night panorama. The break is also musical bliss, a sensual confection of gossamer, night-breeze strings, fresh easy sailing (heart-beat) pace, and melodic (thus not jarring or diverting), whimsical and personal musings via piano and horns. It's a roller-coaster that ends, like many-a great coaster ride, way too soon. Could've gone on for the rest of the album side and, unlike those extended side-long playouts indulged a couple decades later in the disco era, it could've been our delight all the way.

The reverie stops up sharply, even rudely (in contrast to the previous extreme grace) back into focus, a focus of the song's thoughts. Or perhaps from drifting into a world with her back to the world alone. The scene then simplifies to accents behind the chain of thought until, once again, we go along our way and the "picture" closes on an overview shot.

One perception about classic pop is that it was generic and impersonal in the sense of not being particularly individualistic. That charge could apply to a great deal of pop music from any time or genre, to be frank. Speaking of being Frank, give a crack at hearing Frank singing this song in your minds' ear. Yes, this time it works! Night Lights is one Nat specialty that could have been as well sung by Frank Sinatra. Frank even has an ideal manner for it. Lest we think we could swap our King and Chairman, however, we'd have to reckon with the fact that good classic pop could be much more than a great vocal recitation.

This level of classic pop is a rarefied creature: Frank could master this song with ease, but this arrangement wouldn't have been made this way to begin with for anybody but Nat. Nat's is a world in Technicolor, where the listener may blur with the singer to stand either with him or even in his shoes. For Nat, Nelson depicts the scene in a semi-literal directness that probably would have remained more musically abstracted for Frank. A Night Lights for Frank would've been as good of a song, but one without those night lights. Pointless for him to do it, as Frank might've thought after hearing this, and with that we dispense of the notion that classic pop couldn't be particularly individualistic. Or personalized, as they might've put it.

This is another of the jewels in the Nat-Nelson crown, an example of the very height of the classic-pop orchestra and vocal arts, capturing a painting in a fairly conventional three-minute pop song, a music video with no need for any video. The mastery of craft and the highly perceptive synthesis of individual talents involved is as serendipitous as it is rare, a fact time has proven to us.

While Night Lights has shone through the decades, through a re-recording years later to returns in scores of reissues, the next song Nat, Nelson and crew undertook at the session was nearly lost in the shadows of the past. The same mastery that created Night Lights turned just as potently to an even darker night in a stranger place, further from that which was lost, woven into a lament called The Shadows.

Again Nelson's arrangement immediately plunges into rich color and textures, this time setting a sketchy melody among the extreme contrasts of a chime, bass and bass voice background. Nat, in declarative mode, plaintively casts the lyric in long lines (thus also in descriptive mode without specific descriptiveness on any word, these guys just do this stuff, it's a gift) that fly out at the chorus as if they cast shadows that, as the lyric describes, "fall across the sea," and escalate from establishing the point to plunge us into its emotional depths. Nat gradually turns a bit more emphasis to individual points as it goes, once the effect is complete. And then beyond the shadows, the lyric says as the musical and orchestral themes coalesce, "you must return at last / to the shadows of the past."

The break and recapitulation is, if anything, even more bracing. It's hard to imagine why this track wasn't released, but it would remain unheard on the session tape in its box for forty five years.

Nat has the perfect voice for this. It just goes to show (in case anyone missed Armstrong) that having a technically brilliant voice, clarion tones and 5 octaves is of little to no importance in most forms of popular music. It's everything in the service of the singer's expression, as opposed to opera often having a singer giving everything to expression of the music. Nat makes it an advantage not to have a ringing, soaring operatic voice in this song. In the climatic phrase "to the shadows of the past" for example, you get a similar musical effect on strictly emotional levels when he clearly reaches for emphasis of "to," but minus great "operatic" notes you're not blown back, you're still in his grip at it were, all the way through every word before and after.

Off To The Ends of the Earth. There is a temptation I suspect to look back at the time in too few shades of gray. Maybe it's all the smiling at the camera and keeping things strictly polite as a given norm, but there's room for more, a lot of which they thought "you don't talk about" and thus we don't read or hear about much from them.

The mainstream pop of Nat's time could and did cover the area of "you'll never be free!" just as it could cover a romanticized appeal like Unforgettable, ballad of loss like A Blossom Fell, or the gloating tell-off of Who's Sorry Now? There were of course strict contexts to work in - which is still true of today's mainstream - but they could distill a wider range of views in song than is often thought.

I feel that in To The Ends of The Earth, Nat and Nelson and crew are expressing an aspect of love that they are aware is obsessive, compulsive and even scary... but that's not as the protagonist of the song would see it, and the protagonist is, as often the case, the personal point of view the record is working from. In this case the mildly "exotic flavor" of the setting is a quite deliberate association (to them and the audience at the time) with the "savage," "unbridled" passion. This point of view at once allowed a certain admiration or nobility for the "primitive soul in man" while leaving it without saying, so to speak (yay I always wanted to conflict those phrases!) that such a soul might behave in manners not necessarily acceptable to "modern civilized" folks. Such things were within the realm of "romantic" views on matters of the heart. They're not condoning chasing someone obsessively, only expressing that possessive, all-consuming aspect of humanity that can come from love. They do it rather well, it's vigorous and... compulsive, just like the protagonists' feelings.

Audiences of the day understood all that, I suspect, with no discussion required (or wanted). It's only recently that folks far enough removed from the exact society of its day might hear this and go "....umm." It may sound almost like a stalker's song, or at least that "she" may be running for reason, 'cause some of the context has gone missing. Other than the apt comment of a fellow Nat enthusiast, Dale, that "the rush from To the Ends of the Earth is one of life's pleasures," there's little I can add.

I Promise You is right up Nat's alley as a balladeer. Not to say it's such a great song in the context of the company it's keeping here, but in the sense that Nat has a way with sincerity and succinctly stating relatively simple phrases (both lyrically and musically) while fully articulating their meaning. Here he makes a number of turns between pure voice and a dash of wry for relief, enhancing the conversational intimating, and his phrase "in what will seem eternal spring" is a thing apart from the worldly. Nelson's arrangement is merely beautiful. I suspect this one could've been arranged at least as well by Gordon Jenkins. It seems low-key after the previous, but its a nice ballad.

After another jarring entry ala My One Sin (In Life) sets us into a similarly graceful confessional titled The Way I Love You. It wouldn't be a bad fit on Sings For Two In Love. On analysis it's pretty banal. You kind of have to take it at surface value - "don't ask the why or wherefore / just believe it's true" as the lyric states. Enjoy it or pass, it's just a nice straight ballad.

Never Let Me Go brings the session back up to a high standard. It again features a few literal touches from Nelson - a suggested "tick tock" as the lyric states "there'd be a thousand hours in the day..." Not that it's a main feature. The real interest comes from the way the phrases stack and the deft yet always emotionally pertinent way Nat and Nelson navigate them. Nat's timing is ideal here, allowing each of the lines their own introspective thought, while his innately melodic musicality keeps the phrases inter-relating and the song together. It describes an unsettled, dependant state that just isn't easy internally. There's just no way to describe in print how effective Nat is with lines like these, and Nelson's echoing melody on strings is likewise a bliss special to classic pop of this form.

Trivial note: by coinkidink, Never Let Me Go was a song from a movie, and includes the phrase "my flaming heart," which was the title of an earlier movie song Nat had done.

January 21st

- Here I Am

- Unfair

- Make Me

- Sometimes I Wonder

- Once Before

- I'm Willing To Share This With You

- I Need A Plan

- The Story's Old

The tape of the unissued Here I Am was lost and has not been found. While quite unlikely at this point, perhaps someday it will say...

Unfair is a song from a fellow who is professing the realization of his errors to his loved one. Or so it might seem on the surface. It seems to be half internal rumination and half spoken apology. Given the way Nat has with being an internal voice, it seems to my mind to be his voice as spoken to and within himself, partly rumination and partly thoughts of what he might mean to say.

Why oh why was I unfair / to a love that was true?

I brought tears to your eyes / making vows, telling lies

How could I be so unwise

Not to know

I'd be sorry...

But therein lies the point of the song. Atypically enough for the genre, it's not the obvious statements of the lyric that it's all about. For as real as the regret might be, as purely honest and contrite as the protagonist sounds spoken in Nat's considered and sensitive voice, who is it that he thinks of still? Himself. Often can a person benefit from self-reproach without truly realizing their fault, and never quite change their ways for all their regret afterward. Such a person is the one who was Unfair.

Recording wise, Unfair presents a fair bit of confusion. As recorded here at this session, it was completed and then, like Here I Am before it, shelved. Then many years later, it was released with dubious overdubbing, but a partially alternate take was used. When the Bear set finally saw the release of it, we have the presumed original version released for the first time ever and the partial alternate only in the overdubbed version. As yet another piece to the puzzle, Lee Gillette or Nat might've felt they'd been ah, unfair in shelving it; Nat and company re-recorded it a few years after in 1958 for its first release on the album To Whom It May Concern.

Phew. Well then, why the hem-hawin'? It's hardly a top tier masterpiece and there's nothing show-stopping "wrong" with either of the takes from this shelved version. The arrangement of this version and the To Whom remake is nearly identical. This first version sounds "thinner" but that's largely a function of the recording being mono at the Melrose studio vs. stereo at the Tower studio - both sound good, just a different character.

Unusually enough it seems to be Nat's "fault." His reading here is tentative and sticks on properly articulating the words "to the." In the released remake, he sings with a more comfortable, "connected" feel and takes the liberty of pronouncing "to tha" in a rapid pace that makes a definite improvement in the feel of those phrases. But that's in hindsight. It couldn't have been obvious at the time or they'd have remade it right off. How did they know over two years later that it'd come out better? What reminded them? Was it in his concert book or something? Regardless, we can but wonder at the standards they set themselves and their instincts in achieving it so often.

Make Me is reminiscent of Ask Me in having a sense of grandeur about it, if in both cases perhaps a bit overstated. Nat gives as ideal an interpretation as I can imagine, particularly in his ability to maintain a vulnerable honesty even in the comparatively declarative grand manner of this song. Those characteristics work together to lend a sense of due gravity to the phrase "I am a story / as yet to be told." In characteristic literalness, he manages to descriptively mould the phrase "to mould." In characteristic mastery, an awkward passage (accompanying "and you hold the answer") that understandably hits a bit of a blank spot in Nelson's arrangement neither throws him off nor prompts him to plow through it. It all comes off so nicely that terming it "routine" serves to remind one just how fine Nat and Nelson were at this.

Also I admire the taste of the engineer(s); they leave the clarinet way back there, preventing it from lending too "flowery" a note while letting the favored strings bloom (despite their being up front). Darn fine work. The balances are altered slightly for the next track, yet again to ideal effect.

It's noted that it was without temerity to a notable degree that Sometimes I Wonder would lift a slice from Stardust, which was already a golden oldie standard when this song was written. Ah well, no harm done; this is a nice song that does nothing to lessen its enduring inspiration. In fact, could it possibly be that in reminding them of Stardust, we have it to thank for the classic version of that tune that would come later in the year?

My favorite thing in all this is that warm yet fresh, blissful feel this song captures in moments, in common with others of Nat and Nelson such as There Will Never Be Another You. A cloud nine effect. Nelson works a wonderfully apt and perfectly subtle playful feel into the first reading through the passage "and while I'm under this old magic spell..." Ah the way Nat brings the feelings out of the "little" words as clearly as the "large" - "and are you happy...?"

A half-issued and arguably half-steam session so far, but that's nothing for the listener to rue with class talents like these. So far because this was the first half of the session. The best was yet to come.

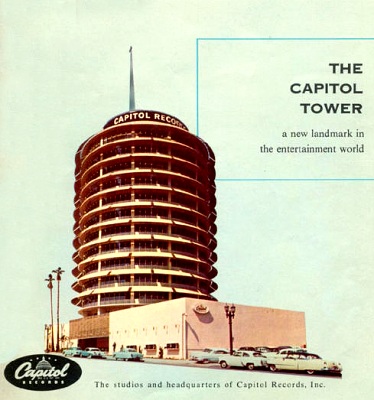

Capitol Records Studios on Melrose Avenue

After a half-hour's break in the session schedule, we return our attention to a recording session resuming at Melrose Avenue, as a kind Los Angeles winter's evening was slowly turning to night around 5:30. Perhaps in the half hour break folks had grabbed a bite for dinner. Now Nat, Nelson Riddle and his pick of available musicians that comprised an orchestra and chorus, producer Lee Gillette and the Capitol Melrose crew reunited and set to work on the first of four songs left on the slate.

Once Before strongly evoked the approach taken once before with The Shadows, suggesting an exotic feel in chords and a deep male and "vapor" female voice chorus. It's not as outright picturesque of course, since this is the realm of reflection. The strangeness of the exotic angle parallels the uneasy experience of a past but abiding longing stirred and being returned to an all too unfamiliar state of renewed wonder.

The chorus is featured, together in a more "straight-ahead" vocal group manner, in providing the effect of a "break" and heading up the recap. The exemplary vocal group arrangement here builds the emotion rather than the more typical practice of easing into an effectively literal "break," letting it lull and attempt to rebuild to a finale. This approach keeps us more engaged in the ebb and flow of emotions that runs throughout the song.

Perfectly one with the firmly articulated arrangement, Nat makes absolute statements that cut through with perfect clarity. In this case that requires conveying a bit more than one dimension. On the positive side of the coin he's earnest about the revelatory moment when he realized love had truly returned into his life. Of the down side of his life prior, he's not shy of making strain show ("and gave her word she'd never go far from me") to stress the grief and alienation, and it's stated with just the right implied blends of hurt and bitterness that, "alone was I thereafter." The sense of literary prose about the wording doesn't detract in the least, as Nat keeps focus on the point "alone" while the rise in melody provides a perfect accent of pathos. Finally there's the reflection on the recovery as he sees it, since it's something unexpectedly regained, not as if this was a person who could seek to replace or forget what he had in the past.

Quite well crafted, this song, with every bit of it perfectly interpreted. This may be romantic in both senses of the term, but it isn't meant to be just "easy listening." They're really aiming for some fine songs here. Likewise the oft-said assertion that Nat King Cole was "always so smooth" and "always made it seem effortless" is not quite true. Tony Bennett or Vic Damone are almost always "so smooth" and "make it seem effortless." Nat didn't completely avoid sliding into a technically rough or raw word or passage, in fact he consciously hit such patches with some frequency and I'm glad he did. He used both the strengths and shortcomings of his voice to advantage, either case held tools he could and did use for the vocal canvas.

Whereas the earlier song Make Me had a grandiose feel, Once Before is on a literally grander scale, having grand sentiments, lyricism, musical ideas and interpretation. After all that, it's a relief to ease next into a more relaxed song. Nat and the vocal group are the features of a sweet and endearing ballad that relates, I'm Willing To Share This With You. The unflinchingly romantic sentiments include:

The heart that I own / the dreams I have known

My love for a life time through

My darling, I'm willing to share this with you.

Nat's way of setting down a clear phrase results in a full sound without other musical support of his phrases. To be sure, this song probably sounded rather old-fashioned stylistically even at the time and is just this side of barbershop quartet to many ears now I suppose. But I feel its unabashed sentiments do express aspects of being in a committed, genuine loving relationship with another person for better or worse that are often dearly missed in more recent times. It's regrettable that it'd so often be derided as so much "corn" and that folks don't tend to think of expressing this sort of thing this directly now. Or even hearing it.

At least as mellow but quite a bit lighter is the next number, I Need A Plan. I can almost see the fellow, dazed yet hopelessly trying to brainstorm, ambling alone along a tree lined path out of the way behind a park, I think it's a relatively warm but breezy autumn evening or early night. Oh yes, the general idea of his general situation:

I need a plan / a magic key

I need it fast / before she gets away from me

Some extra-special way to say, 'I'm wild about her'

'Can't live without her' / I need a plan...

I need a scheme / a magic trick

My brain keeps spinnin' 'round

But nothing seems to click

The personal charm Nat and company bring this lends it character and appeal beyond being a sweet little song. It actually has some of my favorite moments of Nat as a singer. Rather personable, is Nat here, but just try imagining this song from the average singer at the time. You'd likely have all the '50s politeness but with such mannered starch it's not likely they'd venture into the conversational accents Nat does. If they did by some surprising chance, it'd likely result in them dropping out and later back into "singing." The second segment of "...to say 'I'm wild about her. Can't live without her', mm, I need a plan..." has him sliding in and out of a semi-conversational manner without ever interrupting his musical connection, and Nelson deftly slackens up the arrangement around that stretch to help it feel more organic. It's pretty much the ultimate extension of the personable, casual intimation in "classic pop" singing that Bing began. Seems natural as can be to sing it as he does.

Many times over more than a decade by this time, Nat (often with Nelson arranging) had proven to have a special way with the art of "filling out" and personalizing an extremely spare lyric, so that those simple phrases would say everything that needed to be said for just about anyone to join it in reflecting on whatever senses were at the heart of it. That's just what that form of song often aimed to do, and at its best with just the right interpretations, it could work. If it didn't work, you still tended to get the gist of it well enough and at worst you'd usually just have a "nice song."

Nat often chose songs that were pretty extreme in that respect (or their writers wisely picked Nat), such as A Blossom Fell or Annabelle, making it a kind of specialty for him. Few others could do some of those as well as Nat, so perhaps it's little surprise that relatively few "covered" Nat's songs at the time, choosing carefully when they did. The last song of this session was another in that line of classic pop song not likely to flower under anyone's hands save Nat. Again Nat and Nelson worked their magic, this time on the more philosophically informed musings of The Story's Old:

The story's old / as ancient as the sun

No arms can ever hold / a love that wants to run

They say romance / is just a game / that has to end

But you, you played the game / too well, my friend.

The story's old / a million years or so

A love that's cold / is cold as winter snow

I'll try to mend / my broken heart / and hope it never shows

But my heart knows / That's how the story goes.

Accompanying Nat's sober and direct yet melodic and firmly timed vocal is an arrangement from Nelson that informs the message musically. Just as with Nat's vocal, there's the warm feel of an empathetic touch and an understanding of when one can sweep along with time. But you also have these richly voiced melodic lines against a backdrop that's pretty much empty and black but for the plodding and dragging on of indomitable time. Every beautiful phrase swells - and ends. Then the ages old story is told again.

Here, unlike many-a leavin' heartbroken song since, there is no flag-waving about how brave and strong one considers themselves for carrying on, no wailing about how sad one was made, no jealousy, no social self-consciousness, no spite, no anger. Just a reflection with a dearly gained appreciation for the beauty, irony and pain in the truths of the story one has found themselves in. Sometimes that's how the damned old story goes and one knows they're stuck living with it. Period.

The experiences reflected upon in these songs are expressed here about as well as they would ever be. For those who hear them. It so happened the whole session ended up sitting in tape boxes on a shelf, heard by nobody until their first release, long after those who created it had passed away, forty five years later in the rather different era of 2001.

Why? Unfortunately we may never know. It's been speculated that there were some sessions meant for an LP that slipped through the busy schedules. That premise became the Night Lights album. I'm not sure that's the case but it isn't implausible. With greats like Bing, Nat and Frank turning in some of their most refined work and the future for their music looking nothing if not incredibly promising, hindsight might have us see this session as reflecting an era in which classic pop reached its mature zenith. But just as it was reaching that point, a lot of other things were happening that would cut deeply into the system in which Nat was thriving. Things like Elvis Presley and Rock'n'Roll.

Other changes were happening as well. Those tapes didn't sit around at Melrose. Nat had first recorded at Capitol's Melrose studios July 26 1949, and the several years that followed saw his transition into a master popular vocalist which brought new heights of success for himself, Nelson Riddle and everyone at Capitol. Doubtless those were memorable times for Nat and many at Melrose. This was their last session at the old studio.

May 17th

- We Are Americans Too

This song is at least as much a subject as it is a song and it's a subject I humbly submit is much more comprehensively covered by a more qualified author such as Will Friedwald as in his notes to the Bear Family release Stardust. But here's my hap-hazard poke at attempting to offer comments with some thoughts not already expressed by Will's excellent liners.

There are many different ways of assuming one's place in society and asserting one's views. Shout for attention. Selflessly contribute. Defiantly protest. Humbly resign. Angrily battle. Insidiously undermine. Eloquently understate. Aggressively assume. How about proudly articulate? One can find oneself picking up any number of them through ones life, and here Nat attempts the latter in a musical context. If making any statement for the rights of African-Americans in a time more given to condemnation than hyphenation, Nat seems to have chosen a positive, inclusive and affirmative approach that is quite self-consciously calculated to fly with the optimistic and patriotic streaks so distinctive to America of the 1950s.

The monologue by Nat invokes such phrases as "the panorama of progress" and the song is an uplifting jumble of patriotic march and hints of popular jazz band that suits its lyrical summary of African-Americans as a people as deeply invested in the past present and future of their country as any other American. It could almost play along with Walt Disney's Carousel of Progress as we breeze along in a people mover at the World's Fair or Disneyland of '55-'65 with nary a drift, but there's no mistaking that the sentiments behind the message are absolutely sincere. Goodness knows Nat had to deal with more than his share of folks who might've done well to have lent it sincere consideration.

One of my favorite Louis Armstrong standards, I'd like to add is (What Did I Do To Be So) Black And Blue. That song was written by the same songwriters credited with this song, the duo of Eubie Blake and Andy Razaf. Nat is also co-credited, perhaps as there were changes made or ideas added at his behest (that's just a supposition). Blake and Razaf's work was quite familiar to Nat, who recorded a number of their delightful songs over the years.

This session occurred while Capitol studios was in the process of transition from Melrose studio to the landmark Tower, but I can only speculate that partially accounts for the decision to record at United in Nat's old home city of Chicago, a familiar next choice perhaps, as he'd recorded there in the past when not on the west coast. A possibly unfamiliar orchestra (Brian J Farnon Orchestra) is behind him but they're all working from arrangements by the firmly familiar Nelson Riddle. The resulting record didn't see much circulation and presumably little or no airplay however, not being issued beyond a Capitol promotional single at the time.

Then-new Capitol Records Studios aka "The Capitol Tower"

on Hollywood & Vine around 1956

August 15th

- You Can Depend On Me

- Candy

- Sweet Lorraine

- It's Only A Paper Moon

- (Get Your Kicks On) Route 66

Capitol moved from their old studio on Melrose to their Hollywood & Vine Capitol Tower landmark studios early in '56. The new studio was dubbed "The House That Nat Built" and not without good cause. What a delightful quirk then that the first session for Nat King Cole in the Tower was reportedly at his instigation and was to record a relatively intimate jazz oriented session much more in the Trio spirit than his more recent pop hits, pretty darn near the direct opposite of a grand festive orchestral event one might expect for an inaugural session of their celebrated headliner at the grand new facilities.

There's a method to the compliment crowned Cole's seeming caprice however: the session began a project which would become the album After Midnight. Presenting Nat the pianist and jazzman as well as Nat the singer in the context of the Trio augmented by a few select fellow jazz greats, After Midnight showcases Nat's Trio-era talents at their peak. It was an immediate hit and has since been considered to be among the top tier, if not at the top, of all his recordings. It may also be seen as a celebration of the the prime facets that had initially made Nat's career, and indirectly if one so views it, played a key part in making that little studio.

The first session started with a new song titled You Can Depend On Me, opening on an intro featuring some mellow fingerin' by Nat on keys and Collins on guitar that gathers itself into the song proper once Charlie Harris joins on bass and Lee Young on drums, or in this case, brushes. It's nice to start out with an intro like this, since intros were often keen features of many-a Trio cut.

Harry "Sweets" Edison is our most welcomed guest on trumpet. Here he provides some emotional voicings behind Nat's gentle vocal and in a similar state of mind in solo spots. John Collins takes an aloof solo. Lee Young is dead-on in his brush work, providing accompaniment on which one can depend, not too flexible to be loose and not too insistent to be unsympathetic. Harris is fittingly supportive to the end.

There's something refreshing about the way Nat can sing as if making the most personal intimation while in a melodic voice and without affecting a conspicuously quiet manner. His can be the most confidential voice you'll hear, all the more for eschewing overt theatrics for the mediums of melody, time and a knowing understanding. You Can Depend On Me is an example of that gift. One feels the protagonist of the lyric is quite sincere.

Candy is a treat. Like a craving for a confection, the intro can play in a persistent loop in my head. It's neat to hear this augmented Trio work tightly with periodic echoes of the kinds of block chords that the Trio had often made such brilliant use of. Harris' bass is particularly solid here, such a perfect blend of pulse and swing that contributes and supports without ever tripping up a second, and again Young's brush work is such a match it practically breathes the song. Edison's trumpet is sweet citrus. Vocally Nat swings more out of this song that anyone has any business doing, and his piano are runs of honey or chords of rich toffee. Collins digs into a taffy pull (does anyone detect a theme?). If these guys made candy like they handle this song, the stuff would have to be federally regulated. There was a Trio recording of this song on V-Disc transcriptions but it doesn't hold a candle to this version.

How many times must Nat have performed Sweet Lorraine? It was something of a Trio specialty from 'way back and well used by other artists besides. Yet Nat still manages to be with it musically for the vocal, while on the keys Nat gathers it around and moulds it like so much sand in a sand sculptor's wandering hands. I'm not sure where Collins was going (or if he was either) but Edison has some pretty dynamic ideas that are ornately elegant. By the end it's ready to wrap with a nice glow.

If the equivalent in this version of It's Only a Paper Moon can't hope to beat the classic block chords of the Trio's 1943 hit, that's still a nifty turn-and-bounce feature we start off with here. This time both Edison and Collins have some fun bits, but (as we can hear Young digging) Nat's piano has fun and walks away with it. Vocally, Nat had by now proven himself a particular master at making full expressions even from spare lyric and the original of this song was an early monochrome foreshadow that he reminds us of here in full color. Everyone else I've heard sing this hams it by comparison.

We move directly to another Trio great, the iconic Route 66. We're taking the Caddy with a gang of friends here instead of the girlfriend in the flathead Ford, but that's nothing to regret. Harry Edison's piquant turn at the opening theme finds us off to a good start. Nat enjoys changing sixty-six to six six (especially in the closing) and is overall animated lyrically. His piano is strikingly new. There's no mistaking they're enjoying what they're working out here, musically, and no sense that they're warily reworking a tired staple. Collins puts his best, most developed guitar yet into it, and Lee treads a bit more with the sticks here to a deftly discrete yet nicely swinging effect.

This session fulfilled its aims with aplomb. Whether or not it was a one-time celebration in his own way or already planned as the first session to record a summation of the Nat King Cole Trio on album, its success would be reflected in the similarly inspired results of the sessions to come.

September 14th

- Don't Let It Go To Your Head

- You're Lookin' At Me

- Just You, Just Me

- I Was A Little Too Lonely (And You Were A Little Too Late)

Roughly a month after the first session, a second was held, again at the new Tower studios in LA. Another fine group of tunes were completed, perhaps convincing anyone who doubted from the first session that the formula of Trio plus a few suitable guests could create a great album. Perhaps it is a sign of confidence that no Trio classics were revisited in favor of a set of new and old songs not already associated with Nat.

Harry "Sweets" Edison and Lee Young had been the guests in the previous session. Lee was held over for another exciting date while Harry and a trumpet was exchanged for Willie Smith and an alto sax to results just as sweet. Willie is right in vibe with Lee in being a most complimentary voice here, his timing and lines deft and supple, never too long and never too short.

The idea of dressing up the naked Trio with more conventional rhythm seems to date back to the origins of the Trio but was always mutually exclusive, in that the Trio's swing was always affected by the addition. Here at least the swing that the Trio wears makes a fine and flattering fit. The tailoring credits are shared, but the principal credit may belong to Nat perhaps employing his prior experience to advantage, and to producer Lee Gillette for what he doesn't do to the feel the musicians are creating. Well if the Trio was a superb dry rub barbecue that didn't need no sauce added, at least the sauce here is fine indeed!

In the discussion of the previous session, it was noted:

"His can be the most confidential voice you'll hear, all the more for eschewing overt theatrics for the mediums of melody, time and a knowing understanding."

That talent extended itself to the more offensive role of putting an adversary wise in Don't Let It Go To Your Head just as effectively as it applied to a vulnerable romantic lyric like You Can Depend On Me. The protagonist delivers a bit of friendly warning to a naturally optimistic card in order to clear up any potential misunderstanding that his friendly wife might engender, an exchange greatly animated by Nat's obvious enjoyment of the atypical part. Yes, Nat can encompass such somewhat prickly angles to life with just as much personable understanding as the most romantic intimation. But he's not one to let it go to his head, no.

Guitarist John Collins is out of the aloof funk he seems to have had for some of the prior session, putting in some mellow bits that seem more of an afterglow from the prior date than a part of this song. Nat walks backwards through a perfectly suitable solo. Willie goes further, insightfully echoed in points by Nat and Lee's brushwork. Willie's playing under Nat's vocal reprise is free and easy in the best senses. Harris provides ideal support with a supple bass.

The self-directed lament of You're Lookin' At Me is yet another extreme for Nat, carried off just as superbly and without ever breaking the mood. Humbling doesn't cover the unflinchingly frank re-evaluation of the subject Nat so soberly voices. It's not all swingin' novelty, leavin' and the Moon in June in Nat's world, that's for darn sure.

Willie's statement of the intro might as well be on a valve trombone, which strangely enough would be the guest instrument for the next session. Back here, Willie's solo is of a more conventional ballad context and is rather nicely restrained, recalling past chutzpa in one long note and continuing to comment with a shake of the head as it were. Nat underscores Collin's now fully in step solo with fitting humility.

Just You, Just Me is just a simple swinger. Nat's vocal expression shifts from emotional to pretty much strictly concerned with swingin': his real showcase here is at the keys. The piano solo (this kid's good! hehe) strikes me as quite unlike his norm in the Trio era, a bit closer to some of the Piano Style album, and perhaps a new leaning from Basie toward Peterson (albeit in his own very clear polished manner). At any rate it seems to me to be among the clearest examples showing that he's still picking things up and developing on the keys. Lee sticks like friggin' glue every moment while Collins and Willie have their work cut out but still pitch in some good bits.

I Was A Little Too Lonely (And You Were A Little Too Late!) opens with a playful intro and sets Charlie Harris up for a somewhat more noticeable turn on bass. It figures, doesn't it, that one role Nat is not so good at vocally would be that of one who doesn't care, in this case sorta saying "sorry! taa-taa." It comes off more as one giving the brush off precisely because he's ticked because he definitely minds. Oh well; that works too!

Willie enjoys a jaunty solo, exchanging with Collins' most interesting (if brief) spot in the session. Lee is still right on the button, but isn't right on Nat, at least not sure where it's going, and little wonder as Nat's solo is unpredictable and a bit untypical. With a return to Nat's still-irked tell-off supported by propulsive rhythm by Harris and Young, we wrap this session enjoying plenty of flavor to the last bite.

As with the previous, this session could've gone on for a few albums before this listener would be thinking of a break, but at least the few tracks we get are pure choice straight through.

I feel it's clear as well that Nat has reached his maturity as a vocalist by this point. He would continue to develop and change as time went on, but no vocals from this point forward would ever leave me wondering what it might be like had he rerecorded them later in his vocal career. In many of these songs, there isn't a word I'd hear shaded or inflected differently, not even to approach the innate musicality. The closer one listens to some of these, the more perfect one might find the vocal to be.

While they didn't have the luxury of hindsight at the time, somehow I can't help but feel that at least some involved - producer Lee Gillette if not Nat - were noticing that the vocals could be just as rich as his still sublime piano in their way, and that this point would weigh on future choices.

September 19th

- How Little We Know

- Should I?

- Ballerina

This is from a session that may be found to have a striking similarity to a few other sessions, such as the one which would produce Tangerine. Commonalities between them included being arranged by Nelson Riddle, being largely big band based in instrumentation and feel, and a fairly consistent vibe. Vital and vibrant, the brisk scoring and performances make for some lively listening. They're well recorded too (still mono only at this point).

It's hard to say now how it happened that How Little We Know went unreleased for ages. It's first issue may have been on a rare UK EMI LP, The Unreleased Nat King Cole from '87 or so, roughly 30 years after its recording. In my opinion it ranks among the best he cut in that stunning year of 1956. With it's swinging lope and alternating tension and release effectively animating a delightful song, Nat is set to take a keen vocal, which in its playful final phrases one wouldn't mind having continue for a while... Once I'd played it a few times, it just worked under my skin like an itch you can't scratch away. Can't help but think it could have been a hit. But then Nat didn't need another one in '56.

Should I? is also effective, in as much as it leaves me wondering if they should have. ;) For some reason beyond its brevity, it sounds as if some part of it is missing. Anyway. It's a song that was already an oldie and the results here would make for a nice brassy n breezy album cut. But on its own merits, especially in the company it was among in 1956, I can see it being nixed.

Ballerina is a song that has always seemed to have found a bit more favor than I'd lend it. It was issued as a single (over How Little We Know, yet), was performed in at least some of his live sets and even rated a re-recording in stereo years later. Perhaps it was popular and he just plain enjoyed performing it, so that's that. At any rate, it's certainly not a bad song. There's a lot of energy in the band and overall feel. Nat is a fine choice to sing it, as by this point he's added a more biting side to his innately sympathetically oriented palette that embodies a certain irony the lyrics are all about.

September 21st

- Caravan

- The Lonely One

- Blame It On My Youth

- What Is There To Say

This is so exciting. Mm! Besides memorable tunes with distinct melody and time suited for the ideal treatment they receive from a cast of first rate and distinctive musicians, we also find that more than a few tracks feature a distinct feel that enhances the pleasure of the listen further still. Such is the bliss of After Midnight, and perhaps nowhere is the latter quality more keen than the sublime rendition of Caravan.

Originally a Duke Ellington number written in 1936 by Duke and one Juan Tizol, who was then playing the valve trombone in Duke's famed Orchestra, the frankly picturesque Caravan evokes a romantic situation between two folks in a stereotypical North African caravan as perhaps imagined by a Westerner in the nineteenth or twentieth century. As is typical of Duke's music inspired by exotic notions, the inspiration was genuine and there's nothing remotely negative about the result. 62 years on, it remains a delightful ride.

Already a "golden oldie" by the time of the After Midnight project, Caravan had enjoyed long standing popularity in uncounted covers and renditions on records and in concert performed in a bewildering array of styles, including a definitive original recording featuring Juan and more than a few others of enduring excellence. But the guests of the Nat King Cole Trio for this session were a bongo player, Jack Costanzo, and one Juan Tizol. So it seems that perhaps the most famed number to be associated with Juan, Caravan, was an obvious choice to consider covering. Lucky we are that no one shied from the prospect of tackling the well-used song and didn't settle for a perfunctory reading, as they proceeded to cut what easily contends for the title of greatest cover of Caravan ever made, with or without Juan's involvement.

Juan's involvement here is every bit as one might hope, the perfect fellow on the ideal instrument playing the primary melody and integrated into the work so it's as much the cloth this is woven into as it is accompaniment. I might've preferred more solo space for him, but there are at least two good reasons that's not the case. Another extended solo would have come at the expense of the succinct structure that's such an asset to this number, and it could have made his presence more conspicuous as an instrumentalist perhaps at the cost of the seamless musical foundation his part provides.

Nat's vocal is at once romantic and vivacious. His piano solo is just as engaged, running in its fitful bucking patterns as a curved wave in the art of a Moroccan tile block and not unlike a jaunt on the back of the funkiest camel from a nocturnal caravan ever imagined on the back of a matchbook that he might've picked up in some lounge. It's over way, way, way too soon! But then, the pacing not only fits a certain breathless quality of the piece, its also way too easy for the listener to think that even he could've continued that masterful line any further.

Many covers of Caravan have their emphasis on the sinuous melody, usually atop a semi-exotic beating rhythm. This cover serves rhythm as lavishly as it does melody. The parts and playing of on bass couldn't be more ideal at every turn. Far from being an exotic effect, Costanzo's bongos are beautifully and elaborately employed in concert with the drums throughout a surprisingly varied and quite perceptively structured arrangement. Speaking of arrangement, there must have been plenty of collaboration, but as the arranger of Trio material in the past, much of this may be Nat's work. If so it's among his finest, capping many years of numerous elegantly swingin' examples.

Mood and atmosphere hangs in the air around the prosaic still life about The Lonely One, like a quiet bayou trap along the river of Nature Boy. There's something of the piano solo in Nature Boy in Nat's piano solo here as well, but its primary influence is clearly Juan's elegant preceding solo. It's amazing how somber maracas and bongos can be; not exactly the instruments that might spring to mind when you're thinking "somber ballad" but here they are as though dragging along on an ironic funeral march, the soundtrack for the wallflower.

Bongos, by way of Jack Costanzo, were an addition to the Trio for a period in its history, and were not universally appreciated as a particular asset as such. It's been noted elsewhere that some feel the downside to the bongos were a "clip clop" effect that pinned down that singular effect the Trio offered which might be described as rhythm bucking in the clouds. Still, it's a lithe instrument, much less invasive in that respect than drums would tend to be, and Costanzo is a master of the bongo. They did manage to use the bongo to positive effect on a number of occasions, the preceding Caravan among them. Here unfortunately it kinda drags along (or lopes, as its non-fans might say), but as mentioned they make it work.

We return to the most sympathetic brushwork of Lee Young on drums here, while Costanzo packs up his kit and sits the rest out. Juan continues in a supportive role but does take some solo turns as well.

Blame It On My Youth is another rather humbling self-assessment not entirely unlike You're Looking At Me. The underlying theme that this is an affecting moment on that road to maturity is painfully clear, but it's expressed in Nat's innately gentle way and is all the more affecting for it. This time it's more interwoven in the disillusioning lessons from the failure of a romantic relationship, or a hoped for one discovered to be so much self-delusion as much as deception anyway. Rather cheerful to contemplate, just like The Lonely One. And You're Looking At Me from the previous session. Then there's When I Grow Too Old To Dream in the next session. Given the point in his life and career this occurs, it may be considered as a bit of a personal theme, contrasted as it is with the dizzy highs of other numbers. But such reflections and loneliness for some and delights for others would have been thought quite suited for the albums eventual After Midnight banner.

There was little of the classic Trio in this project to my ears, but by now new directions aren't automatically a bad thing. There are some bits of guitar behind Nat's vocals here which are definitely classic Trio in nature though, and Nat's self-accompaniment of his vocal on Blame It On My Youth has instances of what a wonderful talent he has at that, although it is appropriately even more lushly melodic and subtle than usual.

What is there to say about What Is There To Say? I find it pretty lame compared to the others here, the lesser of the package. Can't remember it to comment much, and I just played these recently... ah well. But it's not bad or anything. Spoiled by the accompanying tracks? Very likely. At any rate our musical friends pack up there, having produced some mighty sweet music.